|

|

Matt Damon, right, as Ripley, with Gwyneth Paltrow and Jude Law in the film version of The Talented Mr Ripley, the first story in Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley crime series. |

Fake art, a fastidious psychopath and Banksy's rodent rampage – the week in art

Patricia Highsmith’s manipulative murderer, Michel Houellebecq’s bitter irony and Orhan Pamuk’s mysterious miniaturists feature in our roundup of the best art novels – all in your weekly dispatch

Jonathan Jones

Friday 17 April 2020

Art novel of the week

Ripley Under Ground by Patricia Highsmith

Fastidious psychopath Tom Ripley, a connoisseur who murders to fund the finer things, enters the art world as arch-manipulator of a forgery ring. Fake art results in real death.

Other reading

The Map and the Territory by Michel Houellebecq

Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons and French charcuterie are among the targets of Houellebecq’s bitter irony in this startling instant classic that uses the art scene as an image of contemporary absurdity.

The Masterpiece by Émile Zola

Historical novels are all very well, but Zola was right there on the 1880s Paris art scene when he wrote this shockingly real fiction about his contemporaries the impressionists. The doomed artist who strives to create an impossible beauty is based on his close friend Cézanne.

Blood and Beauty by Sarah Dunant

Serious research and spicy storytelling combine like the ingredients of a negroni in Dunant’s novels about Renaissance Italy. This one gets you up close to the Borgias.

My Name Is Red by Orhan Pamuk

You won’t find a better book about the history of Islamic art than Pamuk’s epic murder mystery set among the miniaturists of 16th-century Istanbul.

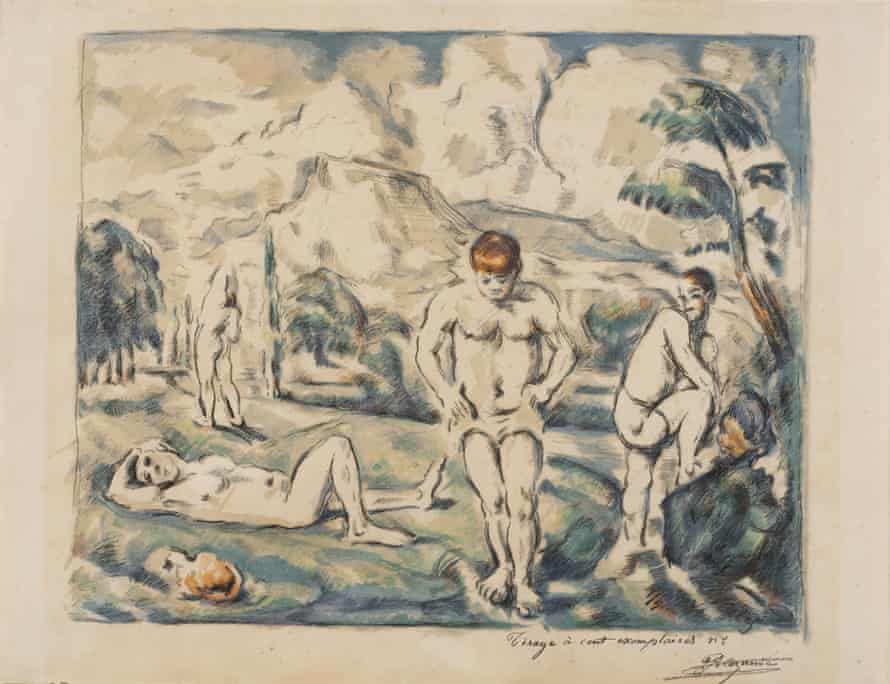

Image of the week

What’s a street artist to do when the streets are locked down? Banksy’s got nothing to keep him busy except create mayhem in his own bathroom. This week he released photographs of what he says is his loo decorated with stencilled rats in a trompe l’œil rodent rampage – swinging from the towel holder, balancing on a mirror frame, perching on a toilet splashed with orangey-brown matter. For these filthy beasts long associated with plague, coronavirus means party time. They are celebrating our decline and fall. Maybe Banksy sees the anarchic potential in a world that has suspended normal business. Read the full article here.

What we learned

Damien Hirst’s Instagram interview has crisps, booze and painted genitalia

Yayoi Kusama’s poetic message to Covid-19: ‘Disappear from this earth’

‘Refuse to be the muse!’: how ArtActivist Barbie is fighting art’s patriarchy online

Art given elastic new life: Winged Bull in the Elephant Case – dance takes over the National Gallery

Sunbathing by the cement factory: Spain’s strangest hotspots – in pictures

‘I need to get as much done as possible - I’ve had cancer’: artists respond to lockdown

Swedish artist and writer Simon Stålenhag on why he likes his dystopias understated

How to support artists struggling in lockdown, from home

Iggy Pop as a Caravaggio painting and a suffocating fish: Sony world photography prize 2020

Online magazine Dezeen, plus galleries and designers organise the first virtual design festival

Mick Rock releases unseen photographs of 1970s rock royalty to raise NHS money

Blocky but beautiful: a gallery of early home computers

The terracotta army breaking the mould of studio potters, from east London

No towers, no tourists: architecture after coronavirus

‘All I hear is my footsteps, and silence’: living in a tourist attraction after lockdown

Fashion under lockdown: eight designers share their workspaces during coronavirus

We remembered Fleet Street photographer John Downing

… and illustrator Tomie de Paola

Who’s that in the diving suit? The great British art quiz from the National Galleries of Scotland

… and what was ‘Daniel Lambert’ a euphemism for? Find out with Compton Verney in Warwickshire

… who is this young royal? Dulwich Picture Gallery, London know – but do you?

… George Stubbs wanted his art to last for ever – how? Find out with National Museums, Liverpool

Masterpiece of the week

Portrait (probably of Battista Fiera) by Lorenzo Costa, circa 1490-95

According to an inscription on the back this is a portrait of Battista Fiera, a doctor who worked in the small Renaissance city state Mantua. Costa has portrayed him in a fittingly clinical way, warts and all, coolly detailing the blemishes and marks of time and care on his face. Doctors 500 years ago didn’t know much about anything we’d call medicine, but they cared for the sick nonetheless. The profession of doctor originates in ancient Greece and Rome. Fiera would have relied largely on classical nostrums for his cures. But he may have got results nonetheless: it’s been claimed Costa gave him this portrait as payment for curing his syphilis.

National Gallery, London.

Don’t forget

To follow us on Twitter: @GdnArtandDesign.

Sign up to the Art Weekly newsletter

If you don’t already receive our regular roundup of art and design news via email, please sign up here.